Plumbing preliminaries

Tuesday, 12th November, 2013

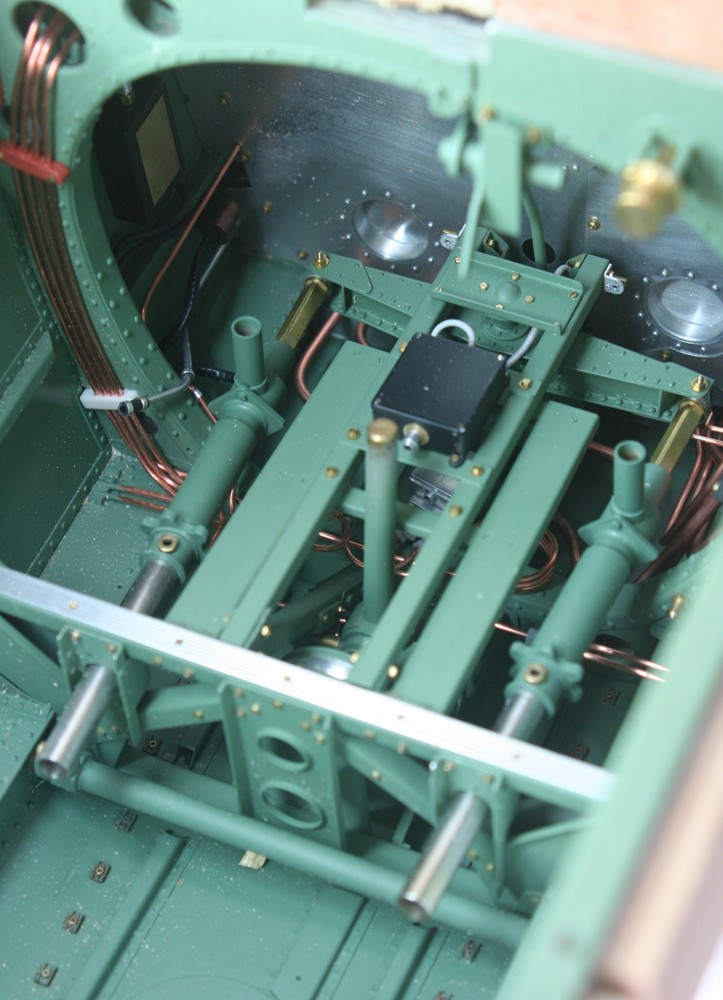

With the successful addition of skin panels to the fuselage underside, I was keen to press on with building up the sides of the cockpit to the level of the datum longeron. But first I had to install some otherwise inaccessible pipe-work, mainly relating to the pneumatic system and occupying the fuselage floor-space beneath the heel-boards.

As countless photographs of Spitfire cockpits reveal, copper pipe of various diameters was used to plumb the pneumatic, hydraulic, oxygen and other systems. When building my previous Spitfire I plundered heavy-duty electrical cable as a source of surrogate copper ‘tube’. However, with stocks getting low and to avoid the mundane task of removing yards of plastic insulation, I decided to purchase fresh supplies in a range of diameters scaling to full-size specification, or a close approximation.

There is little to say about this facet of the cockpit detail, except that it requires full and comprehensive reference sets to determine the pipe runs accurately. Systems diagrams by themselves are generally not enough. While they show schematically where a given pipe run begins and ends, they offer little insight into its actual location or how it conforms physically within the fuselage innards. Installation drawings are the most helpful, followed by photographs, lots of them, although more often than not the latter hide more than they reveal. Research is further complicated by the frequent changes and modifications made to individual systems as they evolve through the various marks. Even within marks, one aircraft can differ from another as a result of systemic or ad hoc modifications made by factories and/or restorers.

Hence at this stage the model maker must expect to spend a disproportionate amount of time pawing over paper. That said, the practical side of things is more demanding of patience than skill. Putting nice even bends in copper wire is relatively easy; putting them in the right places and at the right angles within narrow tollerances is not!

But despite the trial and error involved, installing the plumbing piece-by-piece is highly satisfying, and enlivened by spells on the lathe. Various pipe unions and connectors needed were easily made from brass hexagon. Once in the swing of it, I found I could produce a three-way connector in little more than 15 minutes, including all drilling and turning operations. And with no major load bearing to worry about, solder is unnecessary; if the machined components are sufficiently tight, a tiny drop of cyanoacrylate glue – the very thin variety – gets sucked right in, forming a bond between the clean metal surfaces that is next to impossible to break with the fingers. Similarly, when the various components of a pipe run have been made and dry fitted, the same method can be used to lock the assembly together permanently.

I spent two to three days on this job, concentrating only on those elements that would be hard to install once the cockpit sides had been built up. I drew heavily on photographs in the Montforton book, as well as other sources, and I believe that I have got it mostly right. If not, I take consolation that much of this preliminary detail will be visible hardly all by the time the cockpit is complete.