Oleo strut - Part 1

Tuesday, 5th May, 2015

Back in May 2014 I described making and installing the ‘oleo strut supports’ – a pair of primitive but sturdy tubular brass legs that support the main landing gear. Come April 2015, I began work on the struts themselves.

Paul Montforton’s magnificently comprehensive drawings of the oleos and the many detailed photographs in his book, ‘Spitfire Engineered’ provided everything I needed for this relatively challenging job.

The five basic components are shown in Photo 1. The main cylinder body telescopes outside of its support and is machined (arbitrarily) as three separate pieces, including a short brass section that will carry the scissor lugs. By contrast the bright metal sustaining ram is cut from a length of 1/2-in. chromium plated steel tube. This telescopes inside the tubular support (Photo 2) and it carries a brass axle assembly that includes the lower scissor lugs. I used brass specifically where parts require silver soldering, and since the olio legs will be painted the mixed metals are not an issue.

Photo 3 shows the cylinder body and the thick-walled alloy tube from which it was bored and turned. The lower tapered end was made as a separate piece and it required a milling operation to cut the six vertical flutes. I also needed my milling machine to key the short brass mid-section for use when soldering the lugs.

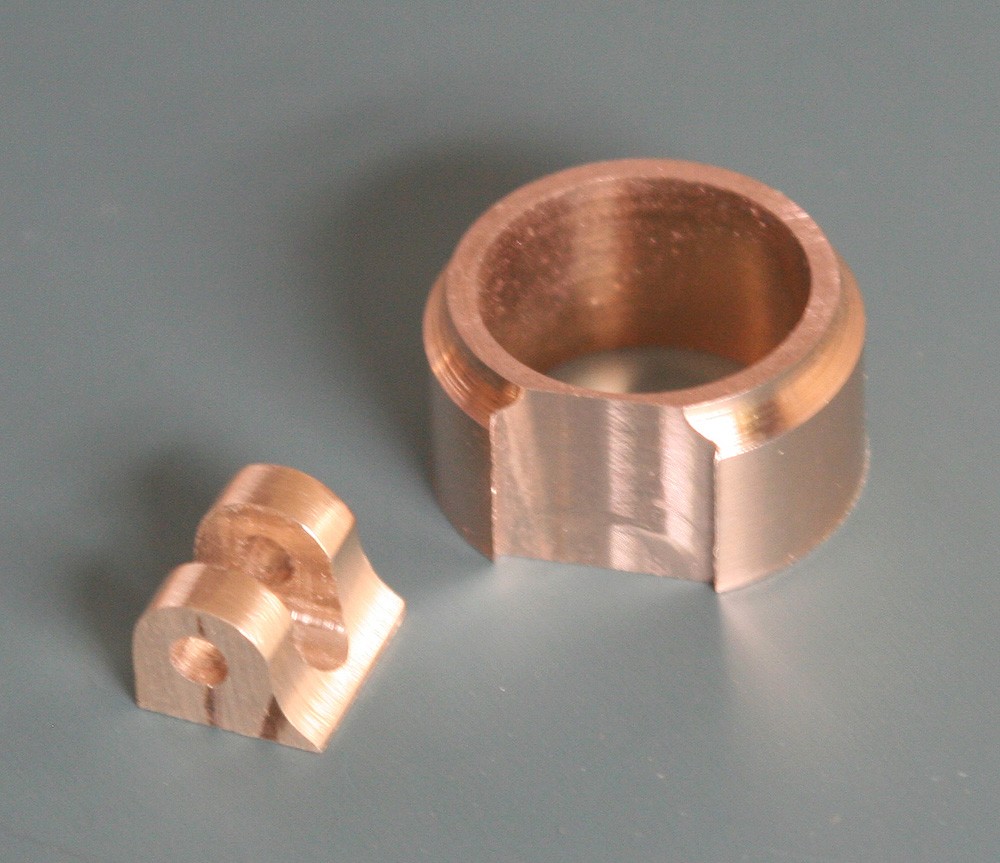

The lugs are milled separately, starting with rectangular section brass bar. The sequence is as follows: The hole is drilled first, then the slot milled with an end cutter. The piece is re-clamped and the curved upper side milled with a side cutter. Finally the front radius is filed by hand using a turned internal steel plug as a guide. The finished piece is parted off in the lathe or with a hacksaw and base milled flat (Photos 4 and 5).

The axle fitting assembly is bored from round brass bar to 1/2-in. internal diameter to accept the ram as a tight push fit, then the outside diameter is machined and the piece parted off. It is then set up in the milling machine and a flat cut on the lower end at exactly 4 degrees from the normal (thus establishing the slight downward angle of the axle), and with the piece still in situ a 3/16-in. or thereabouts pilot hole is drilled at exactly the axle location.

The small brass boss is turned separately, and I gave it a 3/16-in. locating pin with a 1/8-in. pilot hole through it. Once the two parts are silver soldered together the smaller pilot hole is used to drill and tap the piece to receive the axle. The lower scissor lug is made as previously and soft soldered in place so as to prevent re-melting of the previous silver solder (Photo 6).

The final stage is to turn and thread the steel axle and its accompanying steel brake flange. The flange is drilled around its circumference with three sets of three holes for retaining bolts. The two small flats milled on the axle are for use when tightening it with a spanner (Photos 7 and 8).

It goes without saying that both oleo leg assemblies must be precisely matched because even a small discrepancy between them in length, angle of set or oleo extension will become magnified across the wing span of the aircraft, resulting in a visibly skewed sit. Thus throughout the above process I repeatedly test fitted the strut assemblies onto their supports to check for symmetry.

In my next to diary entries I will describe the detailing of the oleo strut assembly and how I made the scissor bars.