Blisters without pain

Sunday, 4th February, 2018

Blisters, in one form or another, litter the skin panels and cowlings of most aircraft, ancient and modern, and for newcomers to scratch building they can present an unnerving challenge.

But blisters are are a lot easier to do than it might appear, and to illustrate this I have chosen a sequence on the upper wing surface of my 1:5 scale Spitfire Mk IX:

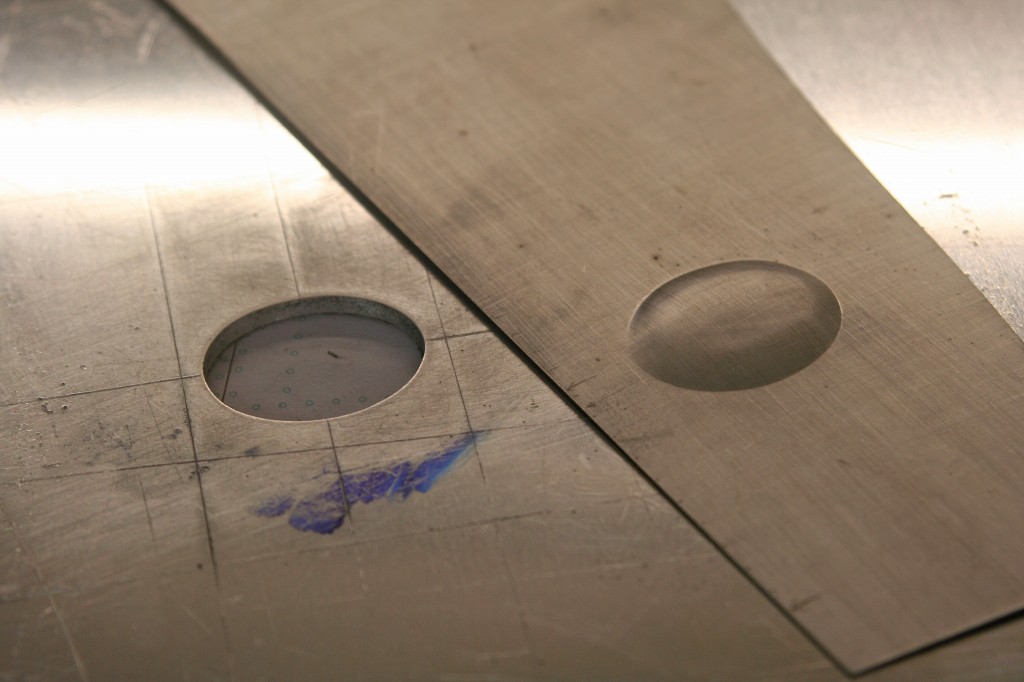

For relatively shallow blisters – say up to around 1/4-in. in scale depth – only the simplest template is needed. I use 1/8-in thick aluminium plate because it is easy to cut and file, but it could equally well be steel or brass.

The first step is to mark the outline of the blister onto the template, so that its internal shape can be cut away. Any sharp edges left on the upper (working) side should be ‘softened’ with a file.

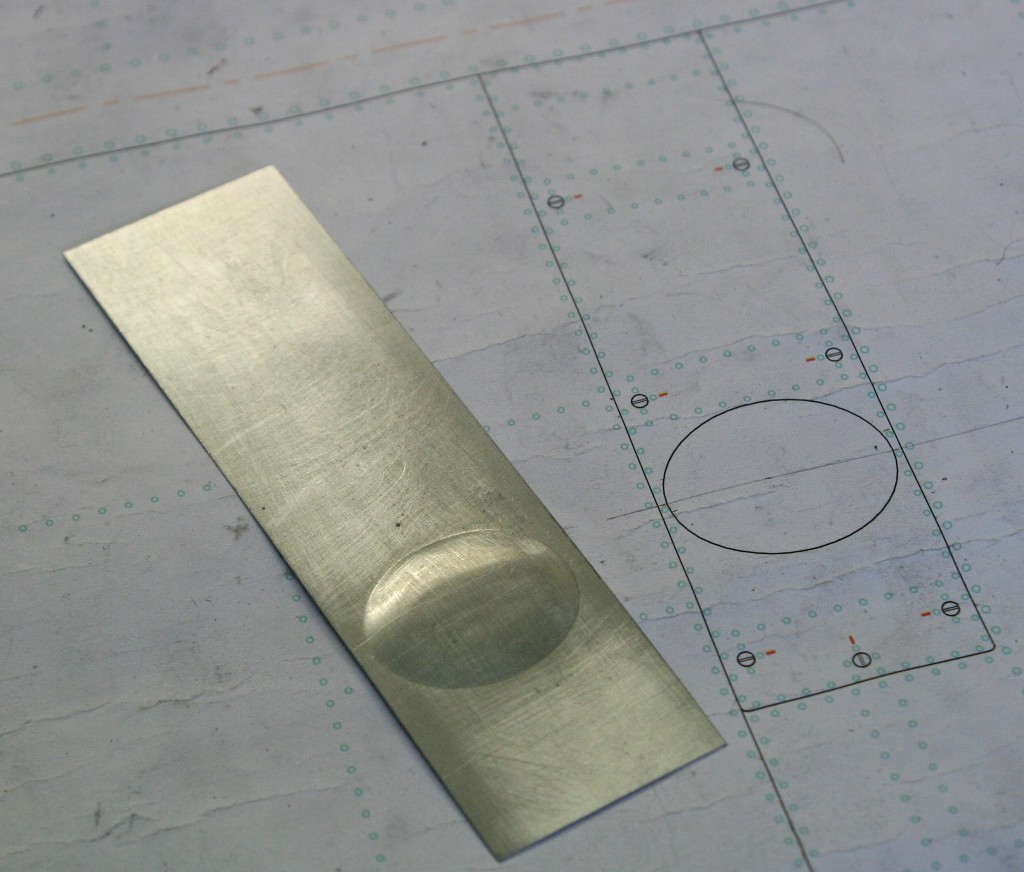

A litho-plate blank is cut larger all round that the finished size of the panel, carefully annealed in immediate area of the blister and then clamped to the template. I usually use the vice jaws for this.

Using a dome-ended wooden dowel of appropriate diameter, the soft printer’s plate is gently and evenly ‘massaged’ down into the oval or tear shaped hole in the template using light circular motions.

To check on progress, the workpiece can be removed from the template to asses the depth and outline of the emergent blister. However, it is vital it is returned and re-clamped in precisely the same position.

For tear drop blisters, burnishing tools in a range of diameters may be required to achieve the asymmetric geometry of the piece.

Once satisfied with the result the litho-plate is removed from the template and its finished outline relative to the blister marked and cut.

The final task is to infill the blister cavity, either with rapid hardening putty or two-part casting resin, or both, according to the size of the cavity. This is important, for without backfilling the soft litho plate would be quickly crushed or damaged.

For beginners, several attempts may be needed before an acceptable result is achieved, but the process is so quick and easy that this is not an impediment.

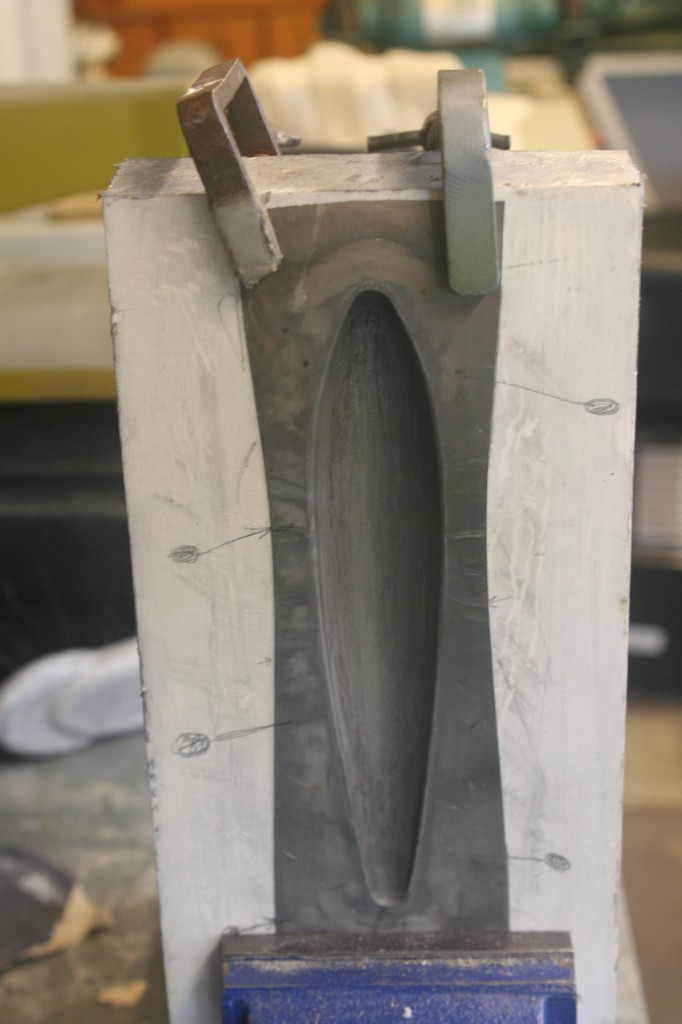

Some blisters – exemplified by the deep elongated ‘bubble’ atop the Spitfire’s cannon – are simply too big for this simple solution. Yet even here the technique is relatively easy:

Firstly, the blister is carved in basswood and primed repeatedly with automotive spray paint. From this male pattern a female mould is cast, using a high impact industrial casting resin.

The annealed litho-plate blank is clamped top and bottom over the open mould. The soft metal is then forced down by stages into the cavity until it ‘grounds’. I use my thumbs to start with and then my hardwood dowels. As the pictures show, these blisters are quite severe, yet it is a testament to the ductile qualities of softened litho plate that even at maximum depth the thinned sheet did not fracture or break.

It is wise with larger blisters to ‘set’ the curved shape of the wing (or fuselage) camber into the finished piece before it is backfilled with resin and filler, otherwise it may become too rigid to conform to the underlying surface at the gluing stage.

There are many features of an aircraft model for which these simple techniques, or variations them, can be employed – proof, I hope, that not all blisters need be painful.